Old China Hands: the author's family in China, 1910-1952

FROM SHANGHAI GRIFFIN TO CHINA HAND, 1910-1920

Site Content

The Anglo-American Oil Company's iron hulled barque Alcides was a familiar sight on the USA-Japan-China run. At the turn of the century, many Old China Hands made their trip out to China in vessels such as these. Oliver Hall sailed on her from Philadelphia to Kobe, Japan, in 1909.

My grandfather, Oliver Hall, was born in Plumstead, Kent, England, in 1888, the son of a gun fitter who worked in the Royal Arsenal in Woolwich. Around the age of 12, he stole some of his fathers tools to sell and ran away to sea. He spent ten years "before the mast" and traveling the wide world before landing in Shanghai in 1910 (the Shanghailander term for such newcomers was a "griffin") and joining the Chinese Maritime Customs, as a watcher. After promotion to third class tidewaiter in 1911, he was posted to the customs station at Lappa, on the western edge of Macau's Inner Harbor. During a battle with Chinese pirates in the Pearl River Delta, he was hit in the head with the recoil of a Nordenfels gun, earning him the sobriquet "Nutty" Hall.

Site Content

New Years Eve, 1915, found Oliver, also known as "Nutty," at this party at the Hong Kong Tsimshatsui Water Police Station. Partial identification: 1-Brown, 2-Oliver Hall, 5-Aitken, 6-Wills, 7-Moss, 8-Wright, 12-Best, 13-O'Reilly, 14-Lanagan, 15-Lanagan, 16-Gordon

While stationed at Lappa, Oliver Hall met the daughter of Chinese merchant Soo Sing (who took the name Sue). They were married in 1919 in Hankow, where Oliver was transferred, with fellow Customs men C.S. Goddard and H.E. Potter as witnesses. They soon found themselves in Chungking, and in the two decades which followed, they would find themselves with a growing family as they moved through Customs stations in Swatow, Tientsin, Lappa, and Shanghai. Dick Hall, the oldest, was born in Macau. Joe, Dorothy (Dolly), and Lillian (Lilly) were born in Swatow, Tom and Charlie in Tientsin, and twins Jim and Pamela in Macau.

AROUND THE PORTS OF CHINA, 1920-1941

Life in the Customs enabled the family to live a very comfortable existence, in marked contrast to the millions of Chinese for whom each day was a struggle. Oliver commanded several revenue launches and gradually rose in rank to Chief Examiner. Amahs and servants helped ensure the household ran smoothly. The children played sports and went to private schools. The adults socialized within their spheres and had their clubs and parties. Oliver would referee football matches. In 1934, the family moved to Shanghai, living on MacGregor Road in the Wayside section. In 1937, during the Sino Japanese War, they moved to the Embankment building. Joe built a homemade canoe which was used to sail in the ponds and lakes in the countryside, as well as to cross the Whangpoo, much to his father's surprise. Dick Hall became an expert swimmer, holding the Southeast Asia record for the butterfly in 1939.

Site Content

A children's Christmas party, Swatow, 1923. Probably held by the Chinese Maritime Customs (CMC) for the children of employees. Oliver Hall is the reclining clown on the left.

"On the China coast in the 1920s and 30s it was pretty common for Customs people to stick together. In Tientsin, where our family lived on Meadows Road, a pleasant residential area of the British Concession, only a few doors from us were the Halls, so we got to know one another. And not just Dick and Joe but their Dad, too, a flamboyant character equally popular with the kids as with the grownups. On that biggest day of the year for us, the Customs Club Christmas party for staff and their families and club members, it was cakes and ice cream galore and a gift for each child when their name was called out by a sonorous Santa Claus whom we all suspected was Mr. Hall himself." -Desmond Power, author of Little Foreign Devil

Site Content

Another party, probably also CMC related. Mid 1930s, possibly Shanghai.

Site Content

Oliver Hall and members of the Tientsin Football Committee, 1932. Picture taken beside the front steps of the Anderson Pavilion. Back row, L to R, Leo Twyford-Thomas, Bob Cooke, Jolly Cooke, Oliver Hall, Peter Lawless (Chief of Police), Jim Lambert.

Site Content

Chinese Maritime Customs Club, Tientsin, 1932.

Partial identification: 1 -Martinella (standing far left), 2 - Oliver Hall (seated far left), 3 -"Mac" MacAuley (seated, second from left), 4 - Inspector Greenslade, Smith (standing seventh from right), 5 -Mezgar (standing second from right), 6 -Lambert (standing on far right).

In late 1938, Oliver Hall was dismissed from the Chinese Maritime Customs after almost thirty years, for an infraction or relatively small misdemeanor. Their father unemployed, oldest sons Dick and Joe followed their fathers footsteps and joined the merchant marine; Oliver's maritime contacts no doubt were helpful in securing ships for them. In 1940, Oliver secured employment with the Alfred Holt Company, the agents for the Blue Funnel Line in the Far East, and the remaining family moved to an apartment in the Holts wharf complex, across the Whangpoo River from the Bund. The children took one of the Holts Wharfs launches or its ferry Aphrodite to and from the Bund to go to school. In the afternoons, Tom, after leaving the Thomas Hanbury School, would watch newsreels of the war in Europe at the British Consulate while waiting for the launch. For entertainment, Holts wharf had its own swimming pool and club as well. Oliver Hall would arrange football matches between the crews of visiting freighters and Holts wharf employees.

Site Content

The Shanghai Bund, circa 1930. The citys "pride and glory," it stood as a statement of solidity and security - security in the sense of protection against violence and disorder (by the treaty powers' gunboats on the Whangpoo River) on the one hand, and safeguards for personal rights, including rights of property, on the other. Few Westerners could have seen it as a precarious perch from which they would be swept away one day. (From Shanghai, A Century of Change in Photographs, 1843-1949, by Lynn Pan, Hai Feng Publishing Company, Hong Kong, China, 1993)

WAR AND INTERNMENT, 1942-1945

Site Content

left: The Rising Sun flag flies over the Bund in occupied Shanghai

On the morning of December 8, 1941, as the Hall children prepared to board the launch to carry them off to school, soldiers of the Empire of Japan arrived to halt the crossing. They handed out biscuits "as hard as rocks" to the kids, who returned home. Meanwhile, excited shouting conveyed the news that Shanghai was in Japanese hands.

Initially, life went on under the occupation. Allied nationals were required to wear armbands Identifying them as such, but restaurants, cinemas, and nightclubs carried on. The family was evicted by the Japanese from Holts Wharf, and moved to a tiny, one room apartment on Avenue Road. In early 1943, most of the British community, including Oliver, was interned. Initially, he was sent to Pootung, across the river from Shanghai, where single men and men married to Asians or neutrals were held. Sue Hall, as a Chinese, was not interned, nor were the children. Dick and Joe Hall were in the USA, where they had joined the merchant marine. Both were to be torpedoed in the Atlantic (on separate ships) but both were to survive the war.

Site Content

Sue Hall, right, with friend Elsie (surname unknown), Shanghai, 1943. The armband "B" was worn by British nationals.

Within a few months, all British Eurasian children over 13 were to be interned, and Dolly, Lilly, and Tom were interned at Lunghwa, were Oliver joined them. Despite the privations of camp, activities and schooling continued. Many internees have commented on the high degree of respect they had for their teachers in camp, many of them missionaries. Dr. Bobby Bloomfield recalls Oliver Hall in the camps:

"I was amazed by Nutty Hall when I met him in the camps at Pootung and Lunghwa. He was an absolute clown, loved by all. He sewed a thousand buttons on a black suit and performed on stage as a Pearly King in a music hall act. He was our version of Stanley Holloway. It was fun to go to Waterloo where the boiled drinking water would be dispensed into our thermos flasks by Nutty Hall. Wherever he went in camp he had a kind and or funny thing to say and often he sang as he walked. Happiness and good cheer emanated from him even in some distressing times."

Site Content

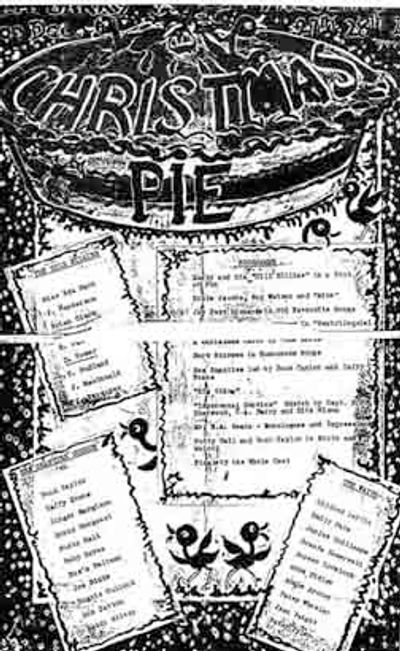

left, the 1943 Christmas show program from Lunghwa CAC

"A good few years after the Halls left Tientsin I found myself in Pootung prison camp in Shanghai, a dark and dreary place, overcrowded, unsanitary, never enough to eat. What kept us going were some fine jazz band musicians and some marvellous ex US vaudeville and English music hall performers. To me, incredibly, Nutty Hall was among them. But it was in Lunghwa camp where we were transferred that I best remember Nutty's stage appearances. His repertoire consisted mostly of comic songs: Henery the Eighth, the Bodys upstairs, Don't have any more, Mrs. Moore, Good Old London Town, but he also sang some soulful ballads such as My Old Dutch. I remember him bringing the house down with his Henery the Eighth." -Desmond Power

The Hall family was now split; Oliver and the middle children were in camp, Dick and Joe were in America, and Sue Hall and the youngest children, Charlie, Jim, and Pamela, were living in occupied Shanghai.

They survived with the help of Chinese friends and neutral foreign nationals. Two Portuguese, David and Eddie Da Souza, tutored the children occasionally. Peanut butter was made by grinding peanuts on a stone wheel and the resulting product was both consumed and sold for money to obtain black market rice. Occasionally, the Japanese would impose a curfew, or display a down allied aircraft as a propaganda measure.

With the war's end, a slow return to normalcy ensued. Residency in the camp continued due to the severe housing shortage, but by the end of the year the family had returned to their apartment above the Butterfield and Swire offices in Holts wharf. But in China, the winds of change were blowing and the family, as well as the entire world of the China Hands, would never again be the same.

TWILIGHT AND FAREWELL, 1946-1952

"We returned to Holts Wharf and everything was great. We had two swimming pools, a football field, tennis court, and a large plot of land where my mother and the amahs would grow vegetables. On the floor below us was a club with a snooker table and bar. Sunday tiffin (lunch) was always a big event and Saturday and Sunday evenings we used to play poker. Winter months the living room always had a coal fire blazing away. We received quite a bit of pocket money and used to go to the movies or the YMCA for swimming or bowling or visit the soda fountain there. The American forces arrived with everything "American" and all the kids became very Americanized. There were always two or three US Navy ships berthed at Holts Wharf. I was often invited on board and had meals with the crew and went out on the boats that were used for liberty. Every evening, all the ships showed a movie with the screen on the godown wall. We used to inquire at each ship what movie was playing that night and then go and see the one we felt was the best. Everything was wonderful. Over the years I often think back to those days and wish the clock could be turned back."

- Jim Hall, recalling the post war years.

Site Content

Units of the American Fleet in Shanghai, August 1945.

The younger children listened to the radio, played in the godowns, or slid down the grain elevators. Dolly departed for nursing studies in Britain. Lilly obtained a job with the British Consulate on the Bund. Tom started an apprenticeship in the Shanghai dockyard just before the Communists entered Shanghai, then left for Liverpool where he became a marine engineer and went to sea. As the Communists drew closer to Shanghai, inflation became rampant, requiring piles of notes to buy anything. After the Communists entered the city, the family moved to a large house on Great Western Road then occupied by Mr. and Mrs. Blackwood, the local manager of Butterfield and Swire. Charlie left in 1950, just before the blockade of Shanghai, as a seaman on a Blue Funnel Line ship. In London, he briefly played football with the Tottenham Hotspur. Lilly married a Swiss national, Otto Dose, and then left, as did so many Westerners at the time. An angry crowd had surrounded Otto and Pamela Hall in their automobile one day and threatened to overturn it. In 1951 Jim left for Hong Kong by train and then traveled onward to Liverpool to join the Blue Funnel line as a seaman. Oliver, Sue, and Pamela moved to Ferguson Road after the Communists requisitioned the house. They finally left, like thousands of others, for Hong Kong in 1952, each person reduced to taking one suitcase only.

Site Content

The Red Army marches into Shanghai, 1949.

Copyright © 2018 Captives-of-Empire.com - All Rights Reserved.